Ensuring DB/DC Plan Success: Fixed Menu Beats a La Carte

The following article is primarily an outtake of a larger presentation delivered Tuesday, October 25, 2022 at the AFP 2022 annual conference in Philadelphia, PA, : “Ensuring DC/DB Plan Success: Beyond Slogans and Gurus.”

Dec 08 2022 | 16 min read – by Steve Deutsch

Fixed Menu Management Approach Beats a La Carte

Using a well-run restaurant as an illustration, I would like to share some tips for improving the options available to retirement and pension plan participants, primarily by improving how the kitchen staff and management, otherwise known as the trustees and boards, operate.

I’m an independent consultant, working with treasury, finance, and HR on defined contribution (DC) and defined benefit (DB) retirement plans: designing, administering, choosing providers through RFPs, implementing, evaluating, and modifying them. I learned my trade at Morningstar, UL Solutions, and as deputy chief investment officer of the Thrift Savings Plan, the largest DC plan in the world. So, I hope you’ll bear with me and my analogy as I outline how governance gaps at the top manifest in poor participation rates and plan performance for employees.

Starting at the Top: Governance

Trustees, board members and committees of retirement plans should be like health inspectors at restaurants, ensuring that laws and minimum standards are observed. But too often we see the watchdogs lapse into defending the restaurant’s existing rating and overreacting to negative Yelp! reviews from participants or stakeholders, without first asking the right questions and obtaining the right answers internally. Sometimes, pension plans don’t have enough well-chosen investment options, or too many overlapping and poorly performing choices. Or plan administrators are not held accountable to timelines and decisions they make while implementing action items.

Plan managers are required to stay up to date on best practice and regulation, and to keep their “customers,” the plan participants, at the center of their decision making. This includes ensuring that participants understand the investment line-up and contribute to receive the maximum benefit. And it extends to the investments themselves – are they keeping pace with the economic and capital markets environment or standing still through inertia or the absence of a formal, responsive investment policy?

Problems at the Bottom:

At present, many of the restaurant managers in our analogy are failing to track their customers or check their reviews, and in the pension world we see this manifest in embarrassingly low 401K participation rates, and low contribution rates and failure to take full advantage of employer contributions among those who do participate.

On the DB side, required contributions at both public and private concerns are often deferred, with negative consequences like unreasonable risk-taking to try to boost performance. Nor are the trustees attending to the diverse needs of their participants, a failure that shows up in significantly different engagement rates based on gender, race, and ability.

Financial illiteracy is so widespread in the United States countries that the pension plan governors are often as ill-equipped as those they’re meant to serve as fiduciaries. That’s how we get investment decisions based on affinity, the idea that if one smart investor has bought in, others will let due diligence take a back seat. We saw this with the Madoff Ponzi scheme back in 2008 and more recently with the institutions that bought into the Allianz Structured Alpha family of funds in 2020 and saw that investment strategy fail.

Large Assets Under Management (AUM) does not equal greater ability

One thing I’ve learned is that biggest is often different from best. Take the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP) for example. More than six million military and civilian public servants rely on the TSP for their retirement and depend on the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board (FRTIB) for oversight. One TSP vehicle, the G Fund, has $237 billion in AUM as of July 2022 and is a bedrock investment for all TSP participants and beneficiaries. Required participant and employer contributions from a vast workforce of civil servants and members of the military make the TSP a very large plan.

Yet remarkably, the G fund has no complete, recent, or regularly updated investment policy statement, even though the FRTIB is mandated to develop such policies in its founding legislation. This fund was started in 1986, and relies on disparate board resolutions from decades ago as its guiding principles.

Consequently, the FRTIB does not have a benchmark index for the “G Fund” to track the performance against, let alone identify a peer group. On the TSP site there are conflicting statements as to whether the G Fund objective is to “Produce a rate of return higher than inflation” or not. Likewise, whether the G Fund is meant to serve as an investment fund or a money market/savings fund is undetermined.

Eating With the Wrong Fork

For the near-final use of the restaurant/menu analogy, both DB and DC plan trustees often fall short in monitoring their investment menus by not using the proper metrics or utensils.

Performance estimates from asset managers like pension funds are surprisingly loose, non-standardized, and not reviewed on a trend basis.

That is, though asset managers observe Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) Institute Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS), asset owners like numerous DB and DC pension plans have been lagging in adopting these same, proven, and predominant standards in their reporting to their participants.

Moreover, reporting to DB and DC Boards and Trustees as well as participants tend to solely address shifting benchmarks and do not delve into the helpful aspect of peer group comparisons of similar strategies and their rankings in these peer groups over time.

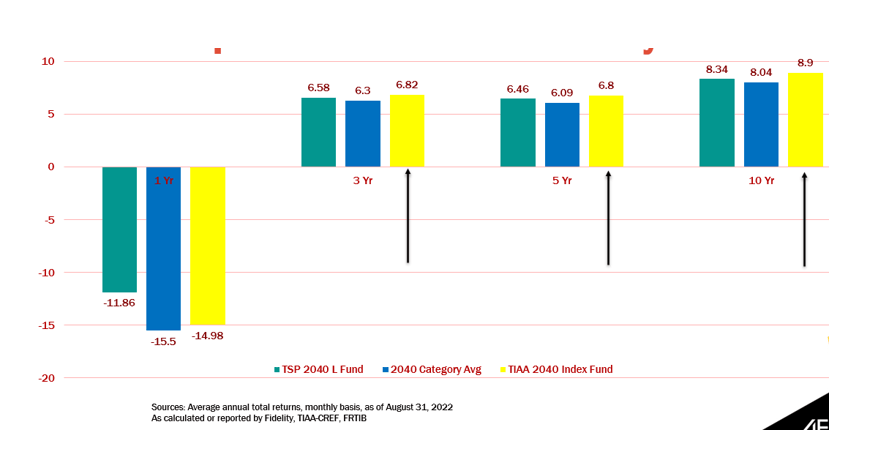

That would lead to some surprising and helpful insight to Board trustees and participants. And it’s quick and easy to identify superior performing private sector competitors like TIAA CREF, which I’ve compared with one of TSP’s target-date funds in the chart below, which are the default and otherwise frequent choice of TSP participants.

This standard type of comparative analysis should be presented by the FRTIB staff to the TSP Board, monthly, as any good plan consultants provide to fiduciaries on a quarterly basis. But the staff of the FRTIB does not act and provide this peer comparison analysis to the Board (and participants) and the Board of Trustees has similarly not asked for it.

Beginning Anew with a Comprehensive Plan Review

To make a DC or DB retirement plan a foundational piece of the total reward equation for recruits and current employees, most plans/companies would benefit from commissioning independent operational/performance/governance/and compliance reviews or audits every three to five years. This would enable board members and trustees to formulate a participant-transparent plan of action to refresh investment choices and up their game in terms of financial education for themselves and plan participants, as well as lifting rates of participation.

Even if they follow these steps, not all DC or DB plans will attract five-star ratings, but at least their participants will have better menu options to choose from and will be better prepared for a healthy retirement. And here, thankfully, ends the analogy.

Despite lots of advantages, TSP L Funds are average performing target dates – many better choices available